Discovering Wonders

Discovering Wonders

Since its founding in 1846, the Smithsonian Institution has been dedicated to enabling scientific discoveries.

British scientist and collector James Smithson (1765–1829) donated the funds to establish the Smithsonian Institution for “the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

Today, his legacy lives on in the work of Smithsonian scientists and curators who push the boundaries of our knowledge with their research, publications, and collections—from astronomy to zoology.

The books Smithsonian Libraries collects document groundbreaking scientific discoveries and technological achievements and serve as valuable sources for scientists and historians.

To live in this age of science without an awareness of its fascinating origins is to miss much of the spirit of its attainments.— Collector Bern Dibner

Why Did He Collect?

Bern Dibner

As a child, Bern Dibner (1897–1988) emigrated from Ukraine to the U.S., where he became a successful electrical engineer and inventor. Curious about Leonardo da Vinci’s incredible scientific and technological achievements, Dibner delved into the study of the history of science and technology, amassing a library of influential works, which he chronicled in his 1955 book, Heralds of Science.

Bern Dibner

Courtesy of the Dibner family

Encouraged by Silvio Bedini, deputy director of the Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History), Dibner donated his collection to the Smithsonian in 1976. Smithsonian Libraries continues to add important works and promote scholarship to this day.

How to Move an Obelisk

Bern Dibner loved reading about remarkable feats of engineering. Swiss engineer Domenico Fontana’s book describes the relocation of a 361-ton granite Egyptian obelisk over a distance of nearly two-and-a-half football fields to St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican City. The task required hundreds of men and took almost a year to complete.

Observing the Heavens

Johannes Hevelius made important scientific discoveries from his state-of-the-art observatory in Poland, which included a 140-foot telescope. His wife, Elisabeth—pictured in the book—was one of the first female astronomers. This copy previously belonged to Bern Dibner’s mentor Herbert McLean Evans.

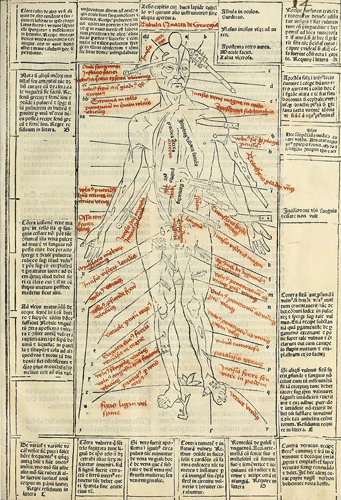

Medieval Medical Manual

Bern Dibner’s collecting went beyond engineering to other fields, including the history of medicine. German physician Joannes de Ketham’s compilation of medieval medical practices includes information on dissection, blood-letting, surgery, and the treatment of diseases, such as the plague.

Everything You Need to Know

Centuries before the first modern encyclopedia, Bartholomaeus Anglicus compiled a compendium of knowledge to educate his students at the University of Paris. De Proprietatibus Rerum (On the Properties of Things) sheds light on how medieval scholars thought about theology, astrology, and the natural sciences.

The Science of Letters

German artist Albrecht Dürer may be best known for his talent as a printmaker, but he was also an accomplished theorist. His influential work on the application of mathematics to the arts includes this study on the geometry of letterforms.

New Experiments

German engineer Otto von Guericke is credited with inventing the vacuum pump, which he used to conduct groundbreaking experiments in physics. This copy of his book Experimenta nova (New experiments) previously belonged to Bern Dibner’s mentor Herbert McLean Evans.

History of Invention

Herbert McLean Evans was a physiologist whose passion for important works in the history of science was an inspiration for Bern Dibner as a collector.

In turn, Dibner served as an inspiration for fellow inventor Bill Lende, whose collection of letters written by influential scientists and inventors now resides in the Smithsonian Libraries’ Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology.

From Mythology to Medicine

Pediatrician J. Bruce Beckwith collected books on teratology, the study of structural deviations in plants and animals. In 2018, his donation deepened our scholarly resources for the history of medicine, complementing the strengths of Bern Dibner’s collection. Ulisse Aldrovandi’s Monstrorum Historia (History of monsters) features illustrations of mythological creatures and reported genetic anomalies.

Joannes de Ketham

Fasciculus medicine

Venice, Italy, 1495

Albrecht Dürer

Institutionum Geometricarum

Paris, 1535

Otto von Guericke

Experimenta nova

Amsterdam, 1672

Ulisse Aldrovandi

Monstrorum Historia

Bologna, Italy, 1642

Why Did They Collect?

Bella C. Landauer and Evelyn Way Kendall

Collectors arrive at their passions in many different ways. Canadian collector Evelyn Way Kendall (1893–1979) may have been influenced by her father’s interest in ballooning.

Evelyn Way Kendall

Norfolk Charitable Trust

Over a period of more than 50 years, she collected hundreds of prints, objects, and books on the early history of flight.

The Birth of Flight

French geologist Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond helped fund the first flight of a manned hot-air balloon, launched by brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier in Paris in 1783. His description of their pioneering experiments popularized hot-air ballooning.

The Golden Age of Flight

As well as trailblazing “firsts,” Evelyn Way Kendall collected ephemeral materials that were often overlooked, including Paul Lyle’s illustrated book documenting the airplanes of “the Golden Age of Flight” in the 1920s and ’30s.

Aeronautical Sheet Music

Bella C. Landauer (1874–1960) took an interest in aviation when her son became a pilot. She scoured music shops to amass a collection of sheet music with aeronautical themes.

Bella C. Landauer

New-York Historical Society

The materials she collected reflect changing musical tastes and the evolution of aviation from hot-air balloons to airplanes.

Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond

Description des expériences de la machine aérostatique de MM. de Montgolfier

Paris, 1783

Paul Lyle

A Book of Airplanes

Racine, Wis., 1930

Why Did They Collect?

Smithsonian Scientists and Curators

Smithsonian scientists and curators are experts in their fields. Many literally wrote the book on their subjects, from grasses to mollusks. The books they collected continue to advance research and scholarship today.

Among these influential collectors are the Smithsonian’s first curator, Spencer Fullerton Baird, explorer William Healey Dall, deep-sea biologist Ted Bayer, and botanists Mary Agnes Chase and Albert Spear Hitchcock.

Mammals

Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823–1887) was a leading authority on North American mammals and birds who served as the Smithsonian’s first curator before becoming its secretary in 1878.

Spencer Fullerton Baird

Smithsonian Institution Archives

This proof copy of Baird’s Mammals of North America features the original hand-colored illustrations used to create the black-and-white prints.

Corals

Smithsonian curator Ted Bayer was an expert on corals. He first began collecting books on the natural sciences in the 1940s to meet his own research needs.

Ted Bayer

National Museum of Natural History

Among his books was Esper’s rare work on corals and sponges with engravings created from the author’s own drawings. Like Esper, Bayer was a talented illustrator.

Shells

William Healey Dall (1845¬–1927) became fascinated with mollusks (invertebrate animals such as shellfish) in high school.

William Healey Dall

Smithsonian Institution Archives

His passion for collecting took him to the wilds of Alaska and to the Smithsonian, where he served as curator of mollusks. Dall’s library included German naturalist Georg Wolfgang Knorr’s rare book on shells.

Grasses

Smithsonian botanist Mary Agnes Chase (1869–1963) was one of the world’s leading experts on grasses. With her colleague Albert Spear Hitchcock (1865–1935), she collected early printed sources on the subject from around the world, including this book by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber, a disciple of Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus—known as “the Father of Taxonomy.”

Mary Agnes Chase

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Albert Spear Hitchcock

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Chase collected books to advance her research, working her way up from a job as a botanical illustrator at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to USDA’s senior botanist and curator of the Smithsonian’s U.S. National Herbarium.

An outspoken advocate for women’s rights, she was jailed several times and threatened with dismissal from USDA for her role in the women’s suffrage movement.

Birds

Eleazar Albin

A Natural History of Birds

London, 1731–1738

Smithsonian scientists and curators also depend on the work of private collectors. Amateur ornithologist Marcia Brady Tucker (1884–1976) donated hundreds of rare books about birds to the Smithsonian, including English naturalist Eleazar Albin’s Natural History of Birds.

Spencer Fullerton Baird

Mammals of North America

Washington, D.C., ca. 1856

Eugen Johann Christoph Esper

Die Pflanzenthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur

Nuremberg, Germany, 1791–1830

Georg Wolfgang Knorr

Les Délices des Yeux et de l'Esprit

Nuremberg, Germany, 1764–1773

Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber

Beschreibung der Gräser

Leipzig, Germany, 1769–1810

Eleazar Albin

A Natural History of Birds

London, 1731–1738

Smithsonian Libraries Collects

Technology

The Smallest Bible in the World

In 2007, the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology used a focused ion beam to create a microscopic version of the Hebrew Bible. More than 1.2 million letters are engraved on a microchip the size of a grain of sugar.

As technologies evolve, there’s no telling what the collections of the future will look like.